David Foster

"We broke the world record. But it’s not just about being the best in the world. It’s when your dad hugs you and kisses you and tells you he loves you — mate, it gives me goose pimples even thinking about it."

"I am so proud of my four kids. And now having a relationship with my grandkids. You talk about being blessed. Winning 186 world titles is fantastic, but without anyone to share it with, it wouldn’t have meant anything."

On the Campbell Town High School footy oval, in the late 1960s, a young David Foster stands with 39 other boys.

The captains scan the group, picking their teams two by two. “You say to yourself, ‘I hope I’m not last picked,’” David recalls. “And all of a sudden, you’re last picked.” David felt like he wasn’t made for school. “I used to have a stutter. I was a fat kid; I copped all the fat jokes,” he says. “The only time I was ever picked first for something was to be the anchor for tug of war! I fit in with people, but I didn’t work as hard as I should have done.” He left school at 15 to work on a farm, uncertain what the future might hold.

But one thing David could definitely do well was chop wood. Tasmania is the home of Australian professional woodchopping, with competitions dating back to the 1870s. David’s father, George, was a world champion woodchopper. David used to lay in bed at night dreaming of winning his own world title.

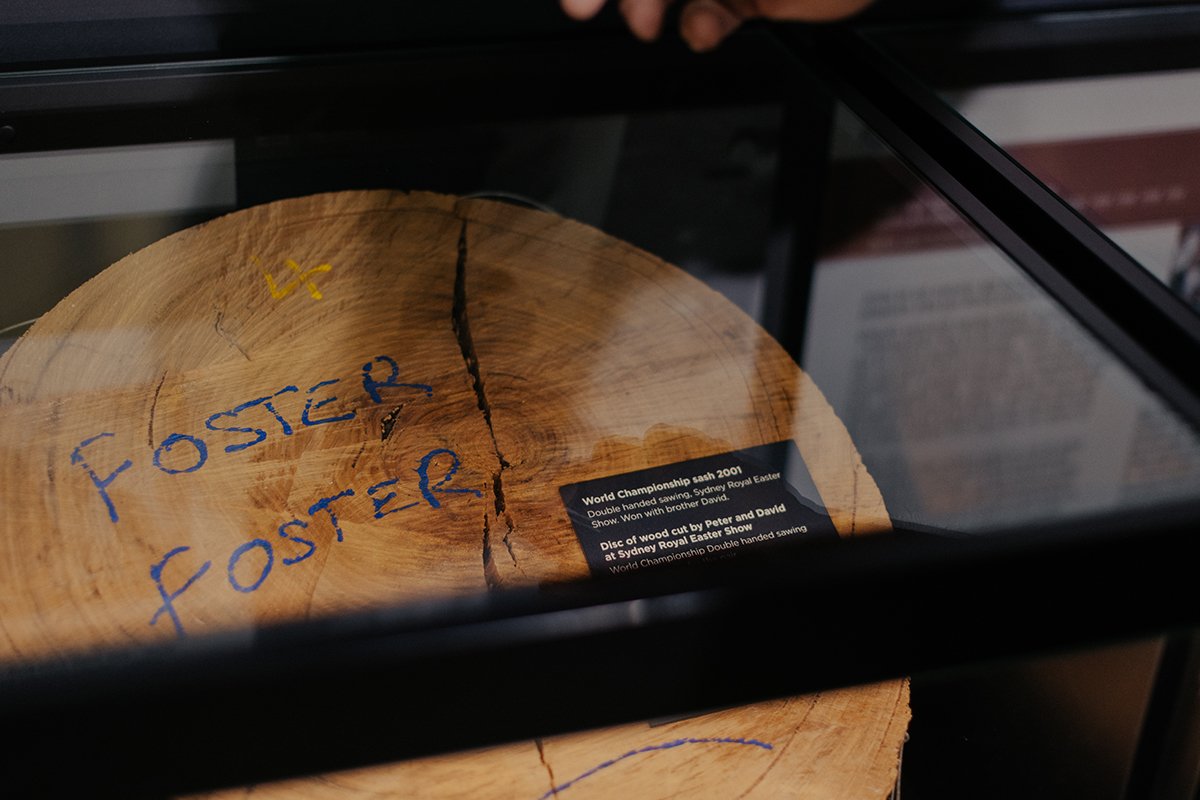

Woodchopping takes strength, precision, and extreme focus. Events include single- and double-handed sawing, standing block, underhand, and tree felling. As he grew up, David competed and won titles in all of them but tree felling. He trained and trained, then trained some more. Then came 1979: the year David won his first world title. He was 22. “The Sydney Show is the Wimbledon of woodchopping,” David explains. “If you win a world title there, you can call yourself the best.” He and George won the double-handed sawing competition — the first father and son ever to win a world title. “We broke the world record. But it’s not just about being the best in the world. It’s when your dad hugs you and kisses you and tells you he loves you — mate, it gives me goose pimples even thinking about it.”

I met a 14-year-old boy — Daniel. He had a brain tumour. He told me how lucky I was not to be able to win a world championship but to compete in one. He passed away six months later. I realised then we’ve got one chance at this life. It wasn’t just about winning. I needed to enjoy the journey.

His wins at the Sydney Show kicked off a massive year for David. He started travelling overseas for competitions and exhibitions. It was also the first time he witnessed children living in poverty. He was so troubled by what he saw, he arrived home vowing to use his woodchopping ability to make a difference. The more he volunteered, the stronger David’s gratitude for the life he’d been given. “I met a 14-year-old boy — Daniel,” he recalls. “He had a brain tumour. He told me how lucky I was not to be able to win a world championship but to compete in one. He passed away six months later. I realised then we’ve got one chance at this life. It wasn’t just about winning. I needed to enjoy the journey.” For David, life is about being inspired by real people every day and being caretakers of this beautiful world we live in.

Woodchopping took David across the world, but his life’s most meaningful moments happened much closer to home. “Children are the greatest joy of any life,” David says. “They change the way you think. You grow as a person.” David’s wife spent three months in hospital when she was pregnant with their twins. The twins made it to full term, but Sally was only 2.24 kg when she was born. As with all of his children, David and Sally were very, very close. But when Sally was a teenager, tension built in their relationship, and she moved to Melbourne. “Unbeknownst to me, she felt differently about life,” David recalls. “Years ago, I would have classified myself as anti-gay. She was too frightened to tell me. When she did, I went to Melbourne to pick her up. I said, ‘You’re my child no matter what.’ You bring your kids into the world. Whoever they turn out to be, you give them your full support.” From that moment, David became a campaigner for LGBTQIA+ rights.

When David was a child, he spent a lot of time with his grandfather, Tom. The door to Tom’s house didn’t have a lock. The toilet was in a shed outside the house, and he used newspaper as toilet paper. He boiled his drinking water. They were humble beginnings, but his grandfather never had a worry in the world, a lesson David never forgot. In their family, it was never about money. “My dad and I went to America in 1985,” David remembers. “We were world champions in Sydney, ready to win a world title in America.” They had been honing their craft, refining their tools and techniques as technology improved, constantly finding ways to stay at the top of their game. “But our crosscut saw wouldn’t cut. We qualified 16th. I thought our trip was wasted.” His dad managed to borrow a saw from the American team. They won three world titles, breaking the world record three times in the same race. David was over the moon, imagining how he’d use his share of the US$3,000 prize money to do something nice for Jan. “And that’s when my dad said, ‘I forgot to tell you something. I told the Americans if we won, they could keep the prize money.’ Now, I could have killed my dad! But he said, ‘We wouldn’t have won anything, no world titles. You might not understand now, but in 20 or 30 years’ time, you will.’”

Twenty-five years later, he did come to understand. Jan had a Category 5 brain aneurysm. In a coma, they flew her to Melbourne, where the neurosurgeon informed David she had a five per cent chance of ever making it home. “I said, ‘Five isn’t a good number, but if you had a five per cent chance to win $10 million, you’d take it. Do whatever you can for her. She deserves it.’” David took two years off work. They lost virtually everything, including their home. David had to stop managing the Axeman’s Hall of Fame in Latrobe, which he had loved and fought for. It was the hardest time he had ever faced. “What focused me was that she was alive, and tomorrow’s another day. You find the positive out of a negative. Try to have a laugh about things. If we wake up in the morning, isn’t that a bonus? And now, she’s at home. I took her back to see that neurosurgeon. She walked into his office, and he hugged her and cried.”

Stephen finished and looked down the line, and he’d beaten the current world champion. I got a tear in my eye. He comes up to me and says, ‘Dad, we’re on track.’ We, not just him. It was one of the most beautiful things.

David is now retired from professional woodchopping. His legacy includes 186 world titles and over 1,800 total titles at various levels. He was Australian Axeman of the Year nine years in a row and captain of the Australian team for 21 years. Reflecting on a career spanning decades and continents, David says, “You never know how life’s going to pan out. If somebody told me, when I left school in Grade 9, how my life would turn out — you can’t dream these things.” The memories of his school days never left him. He now visits schools encouraging young people to value their education. He shares his own story of leaving school and later returning, because he needed the skills when his sporting career took off. More than anything, he remembers the feeling of being picked last. “As captain of the Australian team, I was the one picking people,” he reflects. “I always picked the first two pairs to start with, but then I’d pick someone that might have been left on the shelf, because I can remember what that was like. Once you get success in life, you want to prove to yourself, more than anything, that ‘I am worthy of this.’” This realisation was the biggest driving force in David’s sporting career, and, for him, the source of his success.

At the 2023 Wimbledon of Woodchopping, David watched his son, Stephen, compete in the standing block world title event. “I said to him, ‘Remember what we trained for. Four big hits and then attack it!’ Stephen finished and looked down the line, and he’d beaten the current world champion. I got a tear in my eye. He comes up to me and says, ‘Dad, we’re on track.’ We, not just him. It was one of the most beautiful things.” And then David realised what his dad must have felt, to see him win so many world titles, and for them to win together. “The last thing my mum said before she died was, ‘You have made me proud.’ I don’t reckon I need too much more in this world. I am so proud to have had the ability to win a world title with my dad, to look after my mum. I am so proud of my four kids. And now having a relationship with my grandkids. You talk about being blessed. Winning 186 world titles is fantastic, but without anyone to share it with, it wouldn’t have meant anything.”

We worked with north west Tasmanian photographers Moon Cheese Studio for this Tasmanian story.