Mars Buttfield-Addison

"The idea that it takes a village is true in every aspect. Kids need strategic people placed around them to create that more complex support network. So much of learning is about self-esteem."

"I was an everything kid. I was dinosaurs and lizards and rocks and Egypt and fantasy and space and bugs and trains. It wasn’t ever one at a time; it was all of them, all of the time."

There is a town on the edge of the planet called Strahan, population 697.

Surrounded by cool-temperate rainforest and stormy seas, the nearest land mass to the west is South America, over 10,000 km away. Strahan is one of the best places in Tasmania to view the night sky. Mars Buttfield-Addison dreams of waking up there every morning, walking to the Coffee Shack, and then on to the community science centre she will create with her husband, Paris. “I would talk to kids all day about their weird and wacky questions, and I’d give people little scientific artefacts to take home. There would be a science selfie station, where people could dress up and see themselves as different kinds of scientists. It’s a great, great feeling to watch someone see space for the first time. It doesn’t occur to people very often that we’re hanging on a little rock in the middle of a void, so showing people planets blows their minds,” she explains. “Then I would go home, sip tea in a hammock, and look at the forest. And then I’d go to bed, wake up, and do it all again.”

Mars first became a regular visitor to Tasmania’s west coast with employment and outreach programs run by the University of Tasmania or as part of National Science Week. The more time she spent there, the more she liked towns like Queenstown, Zeehan, and Strahan. As a science communicator, her goal is to inspire people to engage with learning for its own sake. “We don’t know what the future world will look like,” she says. “Learning has to be about more than a getting a particular job. The best thing we can wish for people is that they can choose to do something because it interests them.”

Mars grew up in Logan, south-east Queensland. Her mum was 16 when Mars was born. They moved around a lot, and money was tight. Mars’ extended family played an important role in her early life. “We didn’t know until I was in primary school, but I am autistic, so I didn’t have a typical childhood experience,” Mars says. She did well at school, but it wasn’t until her late teens that she properly met someone who had been to university.

“My earliest memories are of people reading to me,” Mars recalls. “I could read at three and a half, and I was the only kid in my kindergarten class who could read. I read the school library end to end.” Reading was a powerful family ritual. Mars’ stepfather joined the family when she was seven, and her siblings were born not long after. They created a family reading hour after the little ones went to bed. “It wasn’t until then we realised my stepdad had something like dyslexia. Reading out loud was really hard, but he stuck with it because he knew I loved having an activity we could all do together.”

Mars was a voracious learner. “I was an everything kid,” she laughs. “I was dinosaurs and lizards and rocks and Egypt and fantasy and space and bugs and trains. It wasn’t ever one at a time; it was all of them, all of the time.” As she got older, her interests deepened, and her questions became more complex. She soon outpaced her parents’ knowledge in many areas. But they and other adults in her life took her seriously. “My teachers and librarians took special interest. My brand-new stepdad’s brother scrounged parts to build us a computer for home,” she says. Her great-grandmother insisted she never allow herself to get bored. Her mum supported her to try anything and everything, from stargazing to hunting for precious stones. “I did all sorts of sports even though I was very uncoordinated, even highland dancing and roller blading. My mum always took the time to see why I was engaging in different hobbies and valued that.”

High school raised new challenges for Mars. The local schools weren’t well set up for a kid like her, and troubles with extended family made it hard for her to focus in the classroom. Before she knew it, she was out of school and home. She found work in an import-export business, then as a cash dealer in an RSL. But things just weren’t working out. When her great-grandmother – a kindred spirit and one of her earliest caregivers – died, Mars decided she needed a change. She was 23.

“One day, I quit my job, packed my car Rhonda the Honda up to the roof, and drove away to Tasmania, where I’d been on holidays once when I was 17,” Mars recalls. “I was uneducated. I was mentally and physically unhealthy. It was a whim to come here, but it worked.” The atmosphere in Tasmania changed Mars’ life. Rhonda sat in the driveway for six months as Mars walked everywhere. She finally felt a sense of calm. “I’m going to stay here forever,” she says.

Mars re-discovered her love of learning in, what seemed to her, an unlikely place: university. She had some savings, and everyone she met here had gone to the University of Tasmania. She wondered if she should give it a try. “My mother was instrumental. I was like, ‘No, I’m going to feel so stupid. I’ll be the least educated person there. I won’t know what to do.’ But she encouraged me to just go to an open day.” Mars hadn’t finished high school, but the coordinator of the university’s alternative pathways program inspired her to enrol. She was sure she would fail. After six months, she’d done so well, the uni told her to pick a degree and get started.

“I had a full-on crisis,” Mars says. She had no idea what to study. She had always liked STEM but feared she didn’t have a strong enough maths background. A few timely conversations convinced her to try a degree in technology. Her earliest experiences at uni were profound. The academic staff treated her as a peer. “It was this awesome environment,” Mars recalls. “I felt silly trying to write my first line of code surrounded by a bunch of 18-year-olds who had been coding since they were five. But I knew Tasmania was my place. I also knew Tasmania is very community-focused in their hiring and opportunities, so I started trying to meet locals who worked in tech. I volunteered for GovHack, an event where Tasmanian institutions donate data sources for you to hack together solutions in teams over a weekend. That was the first time I met real-world programmers... And also where I met my husband.”

Mars’ husband, Paris, is a founder of Secret Lab, an award-winning Tasmania-based games and creative technology studio. They invited Mars to volunteer at a conference they helped run in Melbourne. It was her first introduction to the Tasmanian niche of the wider tech sphere. In a hyper-competitive industry, the Tasmanian community is different. “It’s small and everyone knows each other really well. There are fewer people, so everyone has to do a bit of everything, which forces you to be creative. As technologists, we also sometimes have to fight against the idea of Tasmania as bespoke, handcrafted, and old-timey, of not being cutting edge. Most people don’t know that there are people down here making world-leading software.”

And then, things took off. “I was at a conference, and I said to someone, ‘we should make machine learning tools in Swift,’ the programming language Apple uses. They turned out to be a senior editor at tech publishing company O’Reilly Media.” They suggested Mars write a book – so she did, while still an undergrad. She became obsessed with the practical applications of machine learning and software development. Writing an algorithm for the sake of it wasn’t enough; she wanted to solve real problems. She embraced the role of support scientist, helping make tools to help other scientists do their jobs. “As a blacksmith is to a knight, so I am to scientists,” Mars explains. “Scientific computing systems need to be really accurate and high-performance but also tailored very specifically to the needs of each domain. To be a developer for that requires you to know a huge range of tools and to work with people whose expertise is vastly different from yours. I don’t know anyone in tech who works on problems as diverse as I do, but I’m loving it.”

So much of learning is about self-esteem. I want to help people understand that particular thing they want to know about, to go away thinking it's possible to understand things they felt like they couldn’t. I want to be part of that for kids, adults, everyone.

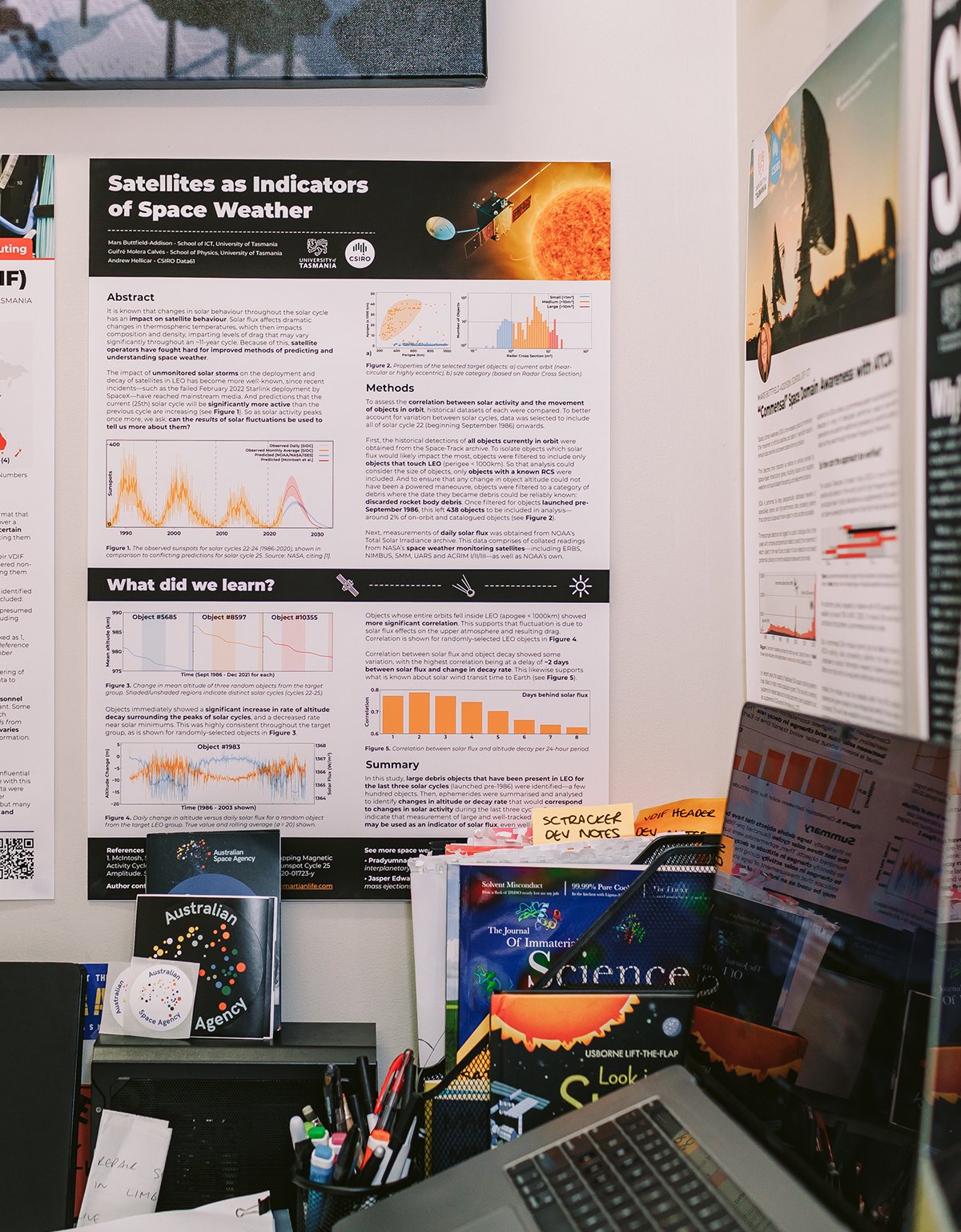

Mars is now working on a PhD, through the University of Tasmania and CSIRO, developing new ways to track and prevent space junk. “When I was little, I was always obsessed with space,” she says. Her project is a combination of her love for astronomy and her passion for environmental conservation. But the more she learns, the more enthusiastic she feels about passing on her knowledge. “When I started being asked to give talks and write books, I rapidly realised I liked teaching people more than just learning myself. Especially things like AI, where a handful of people have made so much money from making it seem like something no one else could understand.” Mars has become a prolific science communicator, involved in everything from the Festival of Bright Ideas to school presentations, and travelling all over the world to teach complex topics to learners of all ages.

For Mars, her path in life has felt a lot like luck: being in the right place at the right time and meeting the right people by accident. And yet her work has meaning and direction, and it is in sharing that she has found her greatest satisfaction. “The idea that it takes a village is true in every aspect. A parent can’t be everything to support the interests of a child who is a whole person outside of you. Kids need strategic people placed around them to create that more complex support network. So much of learning is about self-esteem. I want to help people understand that particular thing they want to know about, to go away thinking it's possible to understand things they felt like they couldn’t. I want to be part of that for kids, adults, everyone.”

We worked with southern Tasmanian photographers Jess Oakenfull and Fred and Hannah for this Tasmanian story.

Special thank you to Warren from the University of Tasmania Mount Pleasant Radio Observatory.